I am worried that Candy Crush is eating our brains. I used to worry that email was eating our brains; now I’m pretty sure it’s that horrible game. My evidence is based on rudely peering at other people’s screens on the subway and the fact that 93-million fellow humans play it every day, driving about $2-million bucks in daily revenue while they’re at it. Candy Crush is extremely habit-forming. So are Facebook, Instagram, Amazon and LinkedIn, and this, according to Nir Eyal, is why they succeed.

If you spent your last performance review quietly plotting to build a habit-forming killer app as your exit strategy, you will want to grab a copy of Eyal’s book, Hooked.

Despite the rampant crushing of banana candies going on in the world, it seems that habit is not to be confused with addiction: it follows a predictable trajectory from nice-to-have, which Eyal compares to vitamins, through to must-haves, which are akin to pain killers. A habit-forming product must scratch an itch and, the really successful ones must keep creating the itch and offering the only solution to relieve it.

Eyal proposes a four-stage Hook Model

1. Trigger

A trigger is an internal or external cue that prompts the user to reach for the product. This can include advertising, but the less precarious and more successful approach is to leverage relationships. When we like a friend’s Facebook page or receive money with PayPal, the easiest way to reciprocate or repeat the experience is to use the same platform. The more we use them, the more we are prompted to keep using them. Other external triggers are found in proprietary apps that companies offer their customers – iTunes is a good example, or your online banking interface, but can also be as simple as subscribing to a newsletter. These owned external triggers allow companies to prompt a user to act.

Internal triggers are more complicated but also much more effective:

“Internal triggers manifest automatically in your mind. Connecting internal triggers with a

product is the brass ring of consumer technology.”

Emotion drives internal triggers. Boredom, a fear of missing out, uncertainty and loneliness are great motivations to jump on Facebook, check your Twitter feed or scroll the endless, meaningless Instagram desert.

If this is your game, I think you would do well to be very, very tight on your user personas. Getting internal triggers right requires a pretty deep understanding of how and where your customers use your products.

2. Action

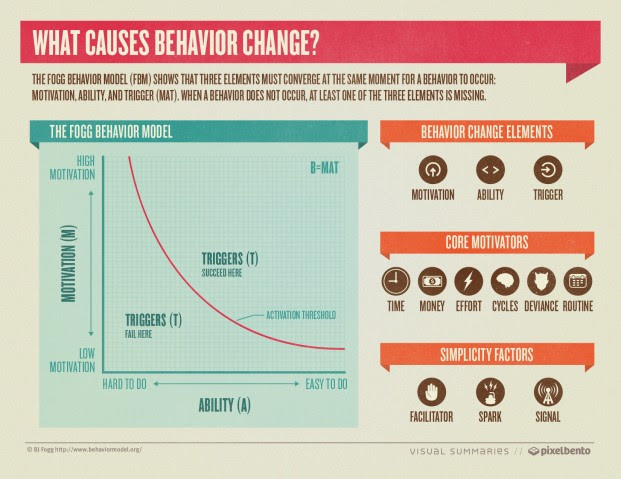

The second stage is taking action based on the trigger. For this, Eyal looks to the Fogg Behaviour Model, which tells us that a given behaviour requires motivation, ability and trigger (B=MAT). This section of the book is a very deep dive into the Fogg Model, and worth it if that’s your thing.

The take-away is that simplicity is key in getting users to behave as you wish: using Facebook or Google credentials as a login for an unrelated site, buttons that let users easily share the pug-meets-gerbil video, or the very simple Google search bar are great examples of what it looks like when we make a behavior ridiculously simple.

If we couple that simplicity with Fogg’s three core motivations — seeking pleasure and avoiding pain; seeking hope and avoiding fear; seeking social acceptance and avoiding social rejection, we have a pretty good shot at getting people to do something useful like flinging birds at pigs.

3. Variable Reward

I’m quite baffled by casinos. I understand the brief thrill of the game, but three watery drinks and a hundred bucks later, this girl is heading to the buffet, leaving the slot machines to the diehards willing to keep pushing the little button and hoping for the matching symbols.

This is a fascinating chapter about the odd ways we seek rewards, and it explains the slot machine thing to me.

It turns out we like three types of reward: those that make us feel part of a tribe, like Facebook or special interest groups. Those rewards that help us acquire the resources we feel we need, such as Pinterest, and slot machines. And those that reward the self with experiences of accomplishment, such as finally getting through email or levelling up in some evil video game.

We are hardwired to crave variable reward and we thrive on the notion of choice. Page 120 has a great summary of a study where panhandlers and charity fundraisers were able to do much better by ending their requests for cash with the phrase “But you are free to accept or refuse.” If you are hearing that phrase, chances are, someone is affirming your ability to choose, overcoming any perceived threats to your autonomy. And you thought you were buying some duct cleaning.

Variable rewards are a powerful driver of habit. Properly matched to the customer, they can create lots of stickiness. Casinos, with their infinite variability, are extreme examples but sites that allow users to like and comment on their members’ activities, or where status can be earned with frequency of use, can engage their communities very effectively.

For marketers, the lesson here is to keep your rewards variable without getting silly about it. Make a product or service that delivers consistently, but find new and varied ways to surprise and delight. So much for that fab customer loyalty program you just rolled out.

4. Investment

This is probably the most surprising thing I learned in Hooked. Truly habitual products demand that the users put something of value into the system to increase the likelihood of their continued use. TripAdvisor is a good example of user investment driving loyalty. So is Twitter. iTunes cleverly demonstrates the concept of stored value — each time someone adds a song to their iTunes library, they strengthen their connection to the platform. LinkedIn works the same way only with personal data as the investment. Reputation, followers and the level of skill required to participate are other forms of stored value.

Pinterest and Snapchat are also driven by user investments of content and do an excellent job of loading the next trigger:

“Habit-forming technologies leverage the user’s past behavior to initiate and external

trigger in the future.”

This is where great loyalty programs build the anticipation of future rewards.

Bottom Line:

This is a great book for anyone trying to understand why they are wasting their lives on Candy Crush or checking Facebook while they’re still sober. It’s a terrific view of how and why some of these unlikely products are succeeding, and it probably offers some useful ideas for anyone planning to build a product or service that will depend on habit for success.

I’m not convinced this is much of a handbook, but I think there is a lot to take away in terms of designing sticky products and great customer loyalty programs. It’s well written in an accessible tone and is a fairly quick read with handy summaries at the end of each chapter.

If you are working on your personas or wondering why they seem to not be helping, you might start here.

Related Posts:

Fixing the Customer Experience Part IV

Toxic Auto-Spamming at Happy Hour

Interesting Things I Found This Week

Nirandfar.com is the author’s blog and is a great source for more stuff on habit and behavior. You can also book a 15-minute chat with Nir.

In case you are lying awake at night wondering how adoption compares across social platforms, this infographic from the folks at Bizcatalyst is an interesting look at the growth of Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter and Instagram.

BizMarketer is Elizabeth Williams

You can reach me at escwilliams@gmail.com

or follow me on Twitter @bizmkter

Reblogged this on sam tumblin favorite artists and more.